What are the challenges to obtaining tariff-free trade entitlements when importing goods which may transit or be stored in a third country?

When the Brexit transition period ended, new barriers for UK-EU trade were introduced.

What was perhaps less discussed and much less expected across the industry has been the requirement to pay duties on goods flows that may have been considered beneficiaries to trade agreements, but, due to the physical route that the goods took whilst transiting between source and destination; or even the requirement to store goods in a third country, a preferential duty relief cannot be availed of.

As we support our clients to review the first 12 months of the new trading landscape it’s clear that the impact that these duties have had on retailers are significant, margin has been reduced and in some cases supply chains are no longer viable.

These challenges arise specifically where retailers source goods from jurisdictions with preferential trading arrangements, such as a Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) or Preferential Tariff Systems, for example the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (‘GSP’), which supports the export market of many developing countries, while seeking to retain pre-Brexit era supply chains.

It’s commonplace in the retail industry to have a lead distribution hub; in either the UK or the EU, that is primarily responsible for shipping goods to their destination of consumption across Europe the Middle East and North Africa (EMEA).

The key feature of Trading Arrangements is what’s known as the ‘principal of territoriality’, which effectively requires goods to remain under customs supervision from the preferential territory of export, throughout the journey to the destination, where preferential tariffs can be claimed.

If the above is assured then there is one of two possible further criteria to meet, every agreement has either a:

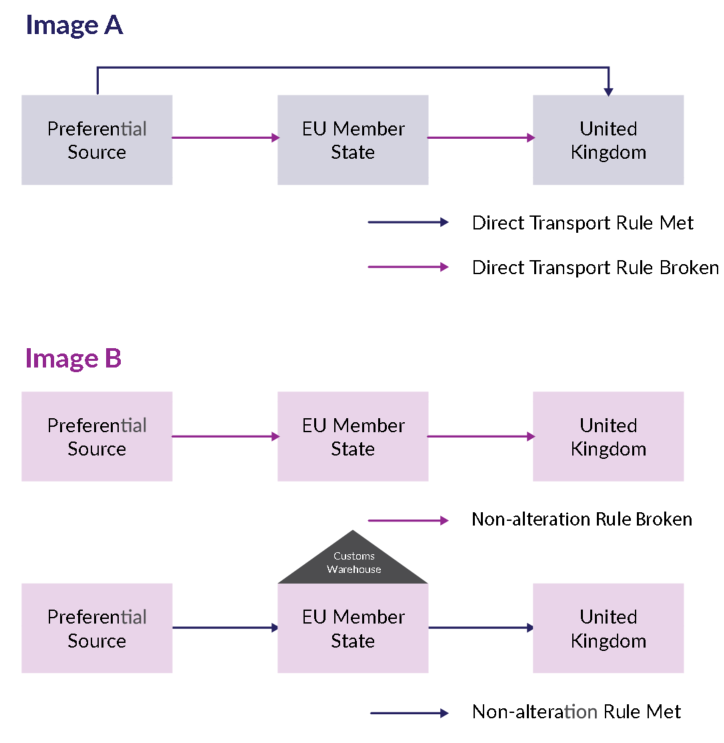

- ‘direct transport’ arrangement – in which case the goods must move under a single shipping document from the territory of export to the destination (Image A)

- ‘non-alteration/non-manipulation’ arrangement – whereby goods can enter a third territory if they always remain under customs supervision. (Image B)

Take the example below:

Before the end of the transition period a retailer may have sourced goods manufactured in a country such as Vietnam; a country that now has an FTA with both the EU and the UK. The goods were shipped direct from source to a distribution hub in Germany, at which point they were imported into free circulation with all duties and taxes paid. These goods would then be free to move through the rest of the EU to the UK subject to no further customs controls.

Consider the same supply chain after 1 January 2021. At the point of import into Germany these goods may not be subject to duty, if they meet the product specific rule of origin in the FTA legislation. If part of this consignment is then required to move on to the UK, then although in principle goods manufactured in these countries may enter at reduced or no tariff due to meeting the product specific rule, the UK importer cannot claim the tariff-free access as the ‘principal of territoriality’ was broken when the goods entered EU free circulation.

The Vietnam-UK FTA has a non-alteration arrangement. Therefore, if we consider a scenario whereby the goods are entered into a Customs Warehouse in Germany; if the goods always remain under customs control when outside of Vietnam or the UK, then it should be possible to claim preferential duties on goods that are further shipped onto the UK.

Finally consider a final scenario whereby the same supply chain exists but the goods have been sourced from South Korea. South Korea has an FTA with both the UK and the EU that contains a direct transport arrangement. Therefore, any movement into Germany; even if entered a Customs Warehousing arrangement, would not meet the requirements of the FTA and therefore goods would not qualify for tariff preference on import into the UK.

This barrier is not insurmountable, however in cases where direct transport agreement exists a change to the physical flow will be necessary. We’ve worked with some businesses who sell product to jurisdictions subject to this requirement in high quantities and high values. The supply chain sees the business source goods from the EU (which originate for customs purposes in the EU) and imports them into a Customs Warehouse in the UK before making a sale to a final customer. Whereby a sale occurs to a customer in a direct transport location the goods can still benefit from the agreement if shipped from the EU. We’ve worked with businesses to obtain opinions from various authorities as to whether it would be permissible to ship the goods subject to a sale back to the EU, before dispatching them to the destination. The authorities stated that this would not break the ‘principle of territoriality’ as the goods always remained in Customs control when outside of the EU and as they would be ultimately shipped from the EU to destination would satisfy the direct transport rule.

The new landscape presents many complexities; however, it is not always necessary for retailers to lose out on the benefits of tariff free trade or to sacrifice their existing supply chains due to this impact of Brexit. However, what is for sure is that importers and exporters will need to address and adapt to this specific element of the new customs environment if they wish to take advantage of the tariff savings which remain available to them.

To find out more about Deloitte and the services they provide to the retail industry, click here.

This article was also published in The Retailer, our quarterly online magazine providing thought-leading insights from BRC experts and Associate Members.