Blogs

Why are British workers increasingly inactive?

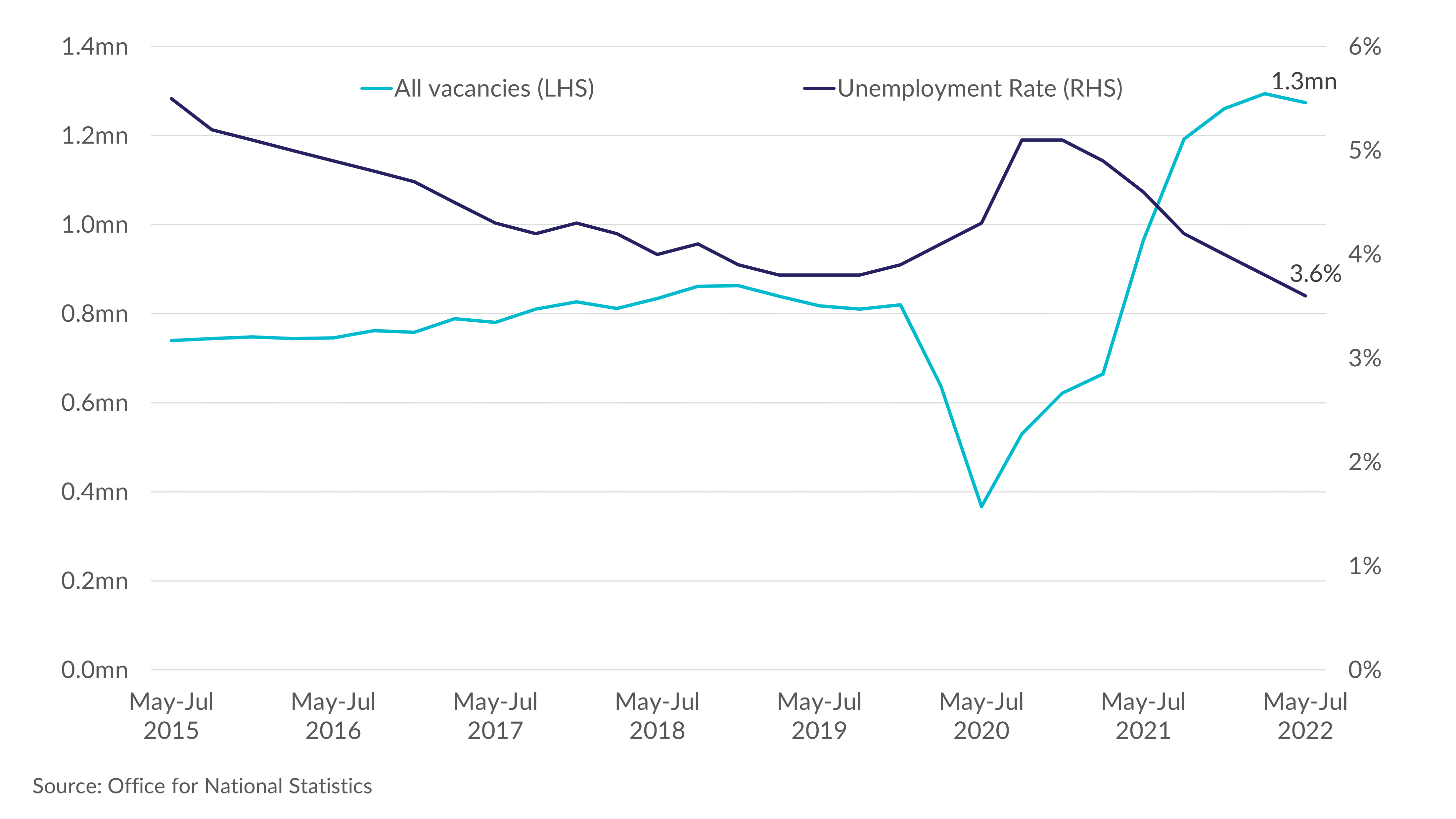

2022 will be remembered for many things: the demise of Queen Elizabeth the second, the symbolic end of the Covid-19 pandemic, war in Europe, and the economic fallout from surging inflation and labour shortages. The UK’s labour market is at its tightest in many decades. Freshly published statistics by the Office for National Statistics, last week, suggest the unemployment rate fell to 3.6%, the lowest since 1974. This is below even pre-pandemic levels and marks what has been a strange economic climate ahead of what the Bank of England forecasts as a long-lasting recession.

Whilst this headline indicator paints a rosy picture of the UK economy (the lowest unemployment in decades does sound very impressive), ONS figures on the number of job vacancies within the economy show they remain near record levels. There are around 1.3 million unfilled job vacancies, of which 100,000 are just in retail. With 1.2 million Britons unemployed, this means that there are more unfilled jobs than workers to fill them.

How has this happened? With firms struggling to attract labour, workers seem not to be very tempted in responding to these advances. There are a few reasons for this predicament – key to note is the smaller pool of labour from which the UK draws from. During the era of free movement, within the EU that is, businesses in the UK could more easily plug labour gaps with workers from mainland Europe, a considerable pool of over 150 million full-time employees.

That pool has now become much smaller, making labour considerably harder to come by at costs firms are hitherto managing to bear. However, whilst Brexit offers important context for the UK, it has not been the only advanced economy to experience labour shortages in the aftermath of the pandemic. Australia, Canada and the United States have all seen an immense tightening in their respective labour markets. There is a common thread that unites these Anglophone countries.

The response to the pandemic from these countries comprised of making a distinction between essential and non-essential industries, and therefore, workers. Whilst many industries such as hospitality, tourism and leisure more broadly were turned on and off, others such as health and social care had to remain on. In the former, job insecurity and low pay saw many workers exit and enter other industries. In the latter, many healthcare professionals faced burnout and high-risk settings. Such occupations are often characterised by low pay and poorer working conditions, ultimately causing many to re-evaluate their career choices.

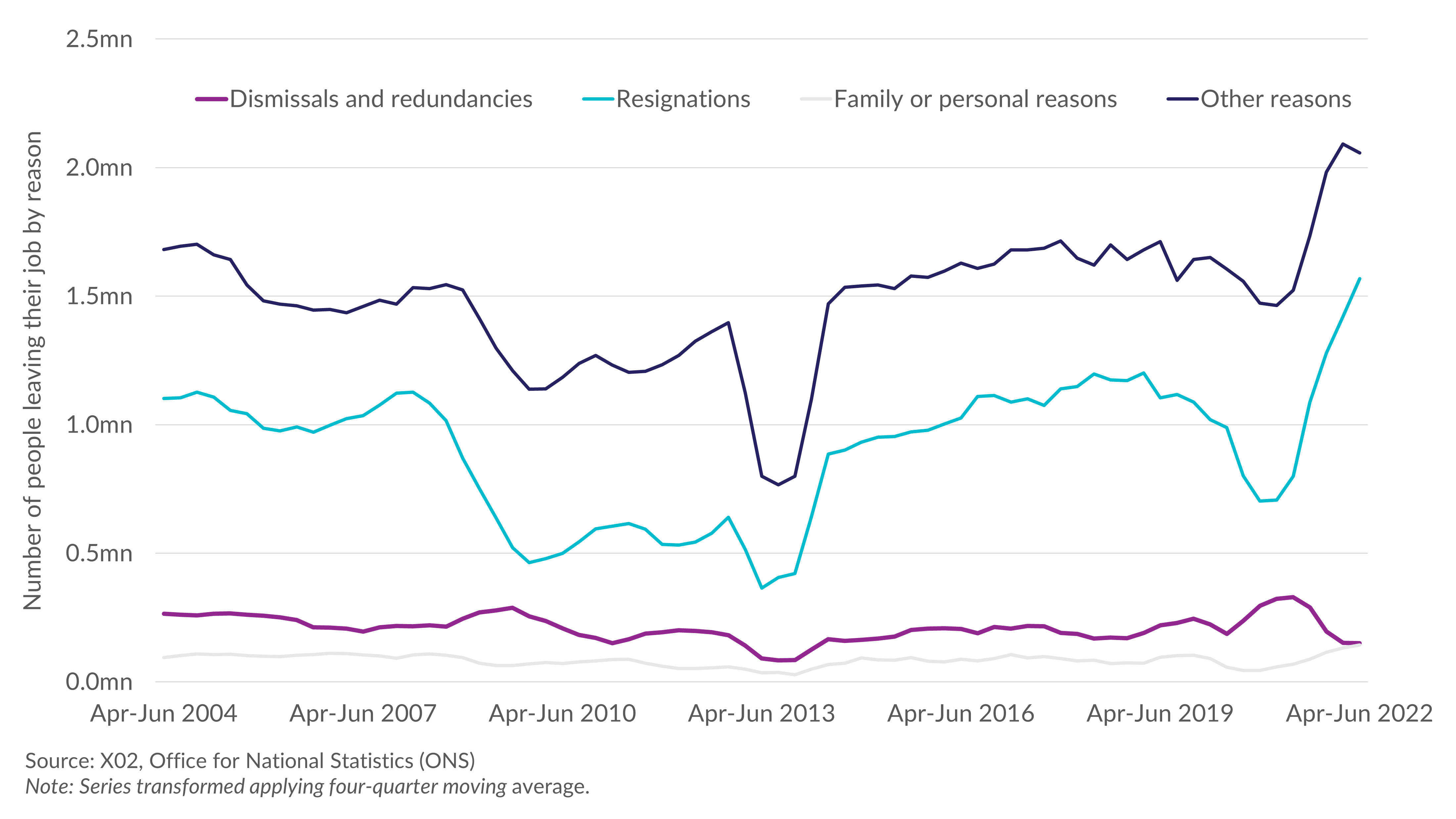

This phenomenon has also manifested itself in the “Great Resignation”, where resignations soared in the UK over the past year, numbering 1.5 million, around half a million more than the pre-pandemic average. With many benefitting from the stronger bargaining position brought about by a tight labour market and having time during the pandemic to re-evaluate their career decisions, many workers quit loudly (before ‘quiet quitting’ became the hot new trend, of course). This is visualised in the graph below, where we can also observe a spike in job moves due to ‘other reasons'. This records those leaving their job for health reasons, education or training. Hence, it is clear that a shift has taken place in the labour market.

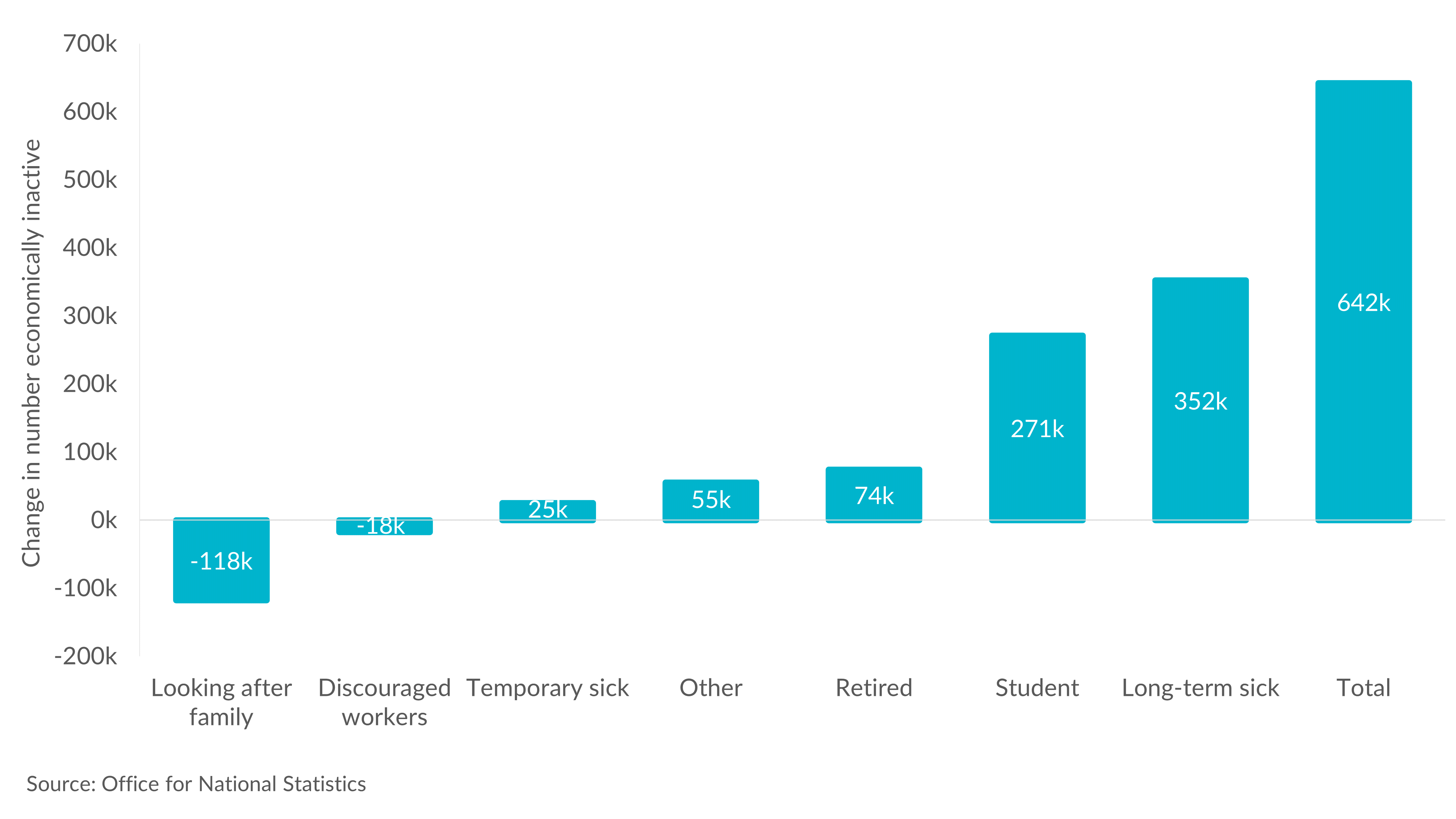

These reasons also find their way into the inactivity figures. Looking at the increase in the number of economically inactive since February 2020, the top two reasons are long-term sickness (a third of which is accounted for by anxiety, depression and stress) as well as those entering education. This means the UK has currently 642,000 fewer economically active individuals. Moreover, 4 in 5 of those inactive do not want a job, the highest on record with a clear downward trend in the number wanting a job. This has exacerbated the labour shortage, and absent government initiatives to help more into work, this situation is unlikely to resolve itself. Resultingly, a tight labour market may be a feature and not a bug, going forward.

A low unemployment rate and high vacancy rate pushes up pay growth, raising the real possibility that inflationary pressures may be further enflamed in the short term. In response, the Bank of England (following its most recent tightening cycle) anticipates unemployment, a lagging indicator, to rise throughout 2023, up to 5.5%. Whilst such a spike in the unemployment rate would ease labour market rigidities, it appears that talent acquirers will need to reconcile a smaller pool of workers from which to draw as the economy emerges from a prolonged shortfall in economic activity. Crucial in this reconciliation is a well overdue investment in automation, upskilling and improving working conditions to address mental health challenges in the workplace.